You may recall this conversation between the Doctor and Clara from ‘The Girl Who Died’:

Clara- “You’re always talking about what you can and can’t do, but you never tell me the rules.”

Doctor- “We’re time travelers. We tread softly. It’s okay to make ripples, but not tidal waves.”

Clara- “You’re a tidal wave.”

Doctor- “Don’t say that.”

Series 9 of Doctor Who beckons questions we didn’t realize needed answering. What happens if the Doctor’s compassion compels him to break his own rules? Is compassion the Doctor’s greatest strength or his Achilles heel? What if the Doctor attempts to defy the Universe at all costs? We’ve gotten glimpses of what could happen in earlier episodes (‘The Waters of Mars’ for instance), however series 9 poignantly and beautifully puts the Doctor firmly in his place.

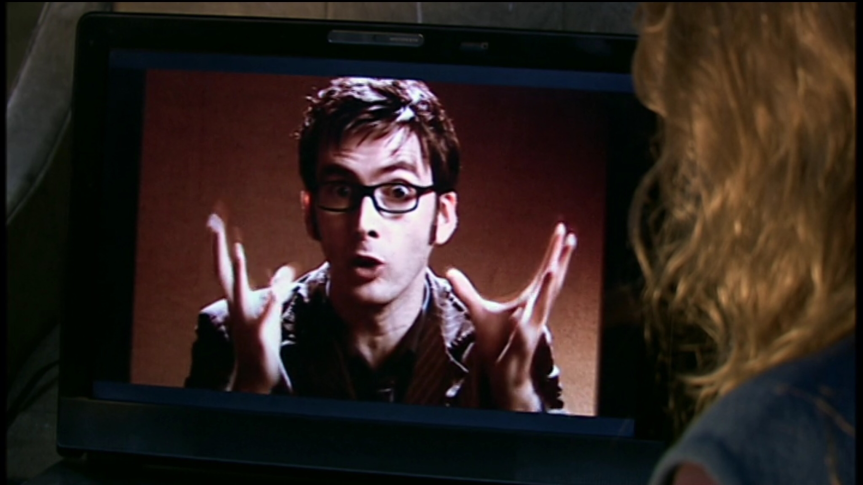

We have followed the Doctor through another journey of triumph and loss, friendships and enemies, but the most important theme of this season is cause and effect. It’s seems as if this season is comprised predominately of conjoined episodes. Whether chronological or not, one episode results in another, or vice versa; the most blatant pair being ‘Under the Lake’/ ‘Before the Flood’. A classic bootstrap paradox in which the Doctor hypothetically asks, “Who composed Beethoven’s Fifth?” In other words, the Doctor outright states that he doesn’t understand all of the inner machinations of time travel and the universe. He is still a passenger of time and without a complete explanation goes along with the flow because he understands the rules. He understands that what he may or may not inadvertently cause into motion will effect all futures from that point. This theme continues to build and to break apart the rest of the season.

Other times, despite his better judgement, he works in harmony with the universe sheerly out of mercy. This is the case when the Doctor is impelled to save Davros even with the knowledge that his actions will enable the creation of the Daleks. “I am going to save my friend. The only way I know how,” says the Doctor to the boy that would grow to be one of his most infamous foes. Missy contrasts the Doctor by matching him in intellect and nonchalance, but lacking his mercy. Davros believes that the Doctor’s mercy clouds his intellect as that is what he eventually utilizes to betray the Doctor. Davros states, “As always, your compassion is your downfall.” The Doctor’s compassion is a force within him that drives him to always win and to love and to rescue the underdog inspite all odds. However, throughout this series we see his compassion betrayed and even enflamed to rage. Is the Doctor’s compassion his friend or his enemy? It’s hard to picture a universe without the Doctor’s compassion, but how is the universe impacted when his compassion outweighs his rules?

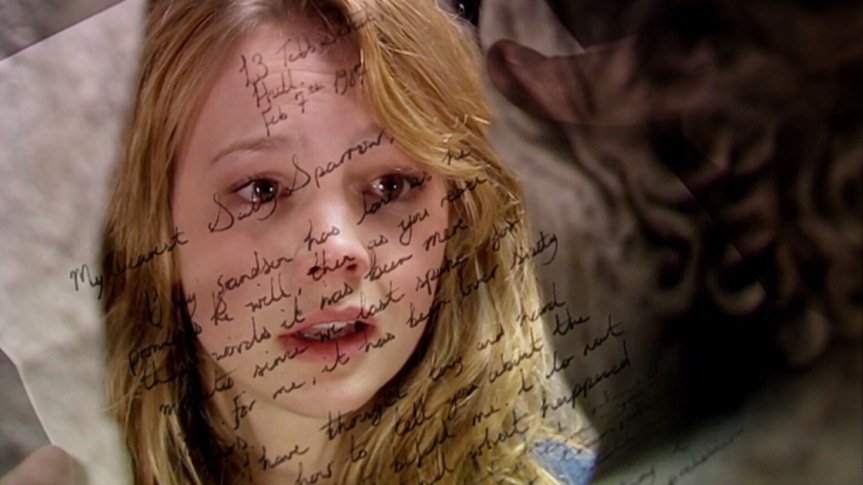

“These people all died hundreds of years before you were even born,” says the Doctor to Clara in ‘The Girl Who Died’ attempting to convince Clara to let time run its course. The thing about Clara and the Doctor is they push each other past logic, relentlessly fighting the tide, to the breaking point of the universe in order to protect those they care about. As usual, they win the war. The Mire are defeated, but the Doctor’s actions directly result in the death of an innocent Viking girl, Ashildr. Clara checks Ashildr’s neck: “No pulse. I think… Doctor is she dead?” While reflecting on current events, the Doctor comes to a revelation: “I can do anything. There’s nothing I can’t do. Nothing. But I’m not supposed to. Ripples. Tidal waves. Rules… I’m the Doctor and I save people. And if anyone happens to be listening and you have any kind of problem with that TO HELL WITH YOU.” The screen pans to Ashildr’s face and ‘hell’ is what that decision inevitably leads them to. The Doctor saves Ashildr, and she is transformed into an immortal who changes her name to Me and lives to see the end of the universe. Ashildr’s death foreshadows the Doctor’s loss/her ressurection causes Clara’s death. Ironically, Clara’s checking of Ashildr’s pulse mocks her own fate.

Interestingly, the Doctor’s realization that his current face, which we previously see worn by a Roman man in ‘The Fires of Pompeii,’ was interpreted by him as a sign that he could bend the rules to his liking. Looking at that very same revelation in retrospect and knowing the tragic outcome of his course of action that day, it’s hard to interpret it as anything but a warning.

Ashildr’s survival leads to Clara’s death, an event the Doctor has made clear he doesn’t think he can cope with. “Look at you with your eyes, you’re never giving up to anger and your kindness and one day the memory of that will hurt so much that I won’t be able to breathe and I’ll do what I always do. I’ll get in my box and I’ll run and I’ll run in case all the pain ever catches up and every place I go it will be there.” The absence of Clara pushes the Doctor to give into his anger. His compassion and his love for his friend fuel a rage that drives the Doctor to places we never thought he could go. In ‘Hell Bent’ he abandons every rule that he ever had and destroys his own reputation, which he’s spent the better part 2000 years building up. It breaks our heart to see our Doctor shoot the very man that had just risked his life by laying down his weapon to save the renowned unarmed war veteran. It’s also prudent to note that when the Doctor revives Ashildr he arrogantly assumes that time will heal itself and work itself out. Frozen between one heartbeat and her last, Clara has to convince the doctor to let her go, lest he irrevocably damage the universe any further.

Clara- “What if one last heartbeat’s all I’ve got? What if time isn’t healing? What if the universe needs me to die?”

Doctor- “The universe is over – it doesn’t have a say anymore! We’re standing on the last ember. The last fragment of everything that ever was. As of this moment, I am answerable to no one!”

And there at the end of the universe, we find Me watching the stars die. She explains to the Doctor that sadness and beauty are the yin and yang to the life of a mayfly, something the Doctor once taught her. They have a conversation about Clara’s death that draws a stark parallel to what would have been Ashildr’s death. Just as when the Doctor told Clara that the Viking village perished hundreds of years before she was even born, Me tells the Doctor that Clara has been dead for billions of years. She brings to the Doctor’s attention that Clara died for “who she was and what she loved. She fell where she stood. It was sad and it was beautiful and it is over. We have no right to change who she was.” This is reminiscent of the Viking girl who stood up to an alien race for who she was and what she loved, and it is clear that Me does not want the Doctor to repeat his folly. The Doctor is reminded, regrettably, that he must confine himself to the rules of the universe.

Our journey ends in what only seems appropriate; the Doctor’s memory is wiped of Clara. Left with only a song that encapsules a lifetime of memories and friendship, the Doctor forgets a companion for the first time. In his last moments with her, he accepts her death and admits that he has gone too far, breaking all his own rules, destroying his reputation, and risking the Universe.

“Run like hell. Run like hell because you always need to. Laugh at everything because it’s always funny. Never be cruel and never be cowardly and if you ever are always make amends. Never eat pears – they’re too squishy and they always get your chin wet. Write that one down, it’s quite important. It’s okay, it’s okay. I went too far. Broke all my own rules. I became the hybrid. This is right. I accept it. Smile for me. Go on, Clara Oswald. One last time. It’s okay, don’t you worry. I’ll remember you.”

Of course we know that he doesn’t remember her, making Clara’s first words to the Doctor all the more poetic: “Run you clever boy, and remember.”